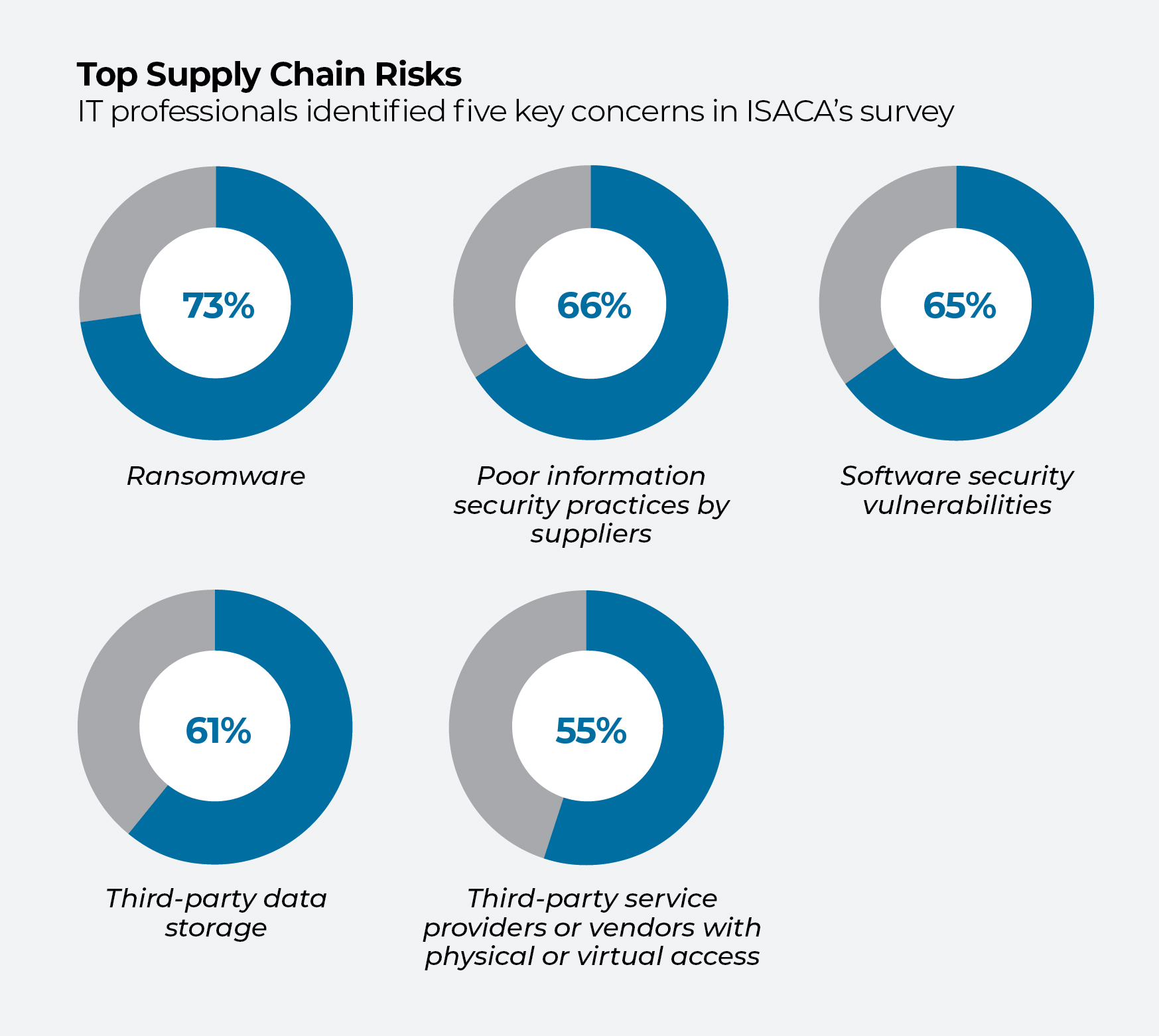

ISACA Survey: Supply Chain Security Risks Are Rising

IT professionals have seen the future, and it looks as though even more sophisticated hacks than SolarWinds are on the horizon. That’s sobering, but there’s good news, too.

One in four companies experienced a supply chain attack over the past 12 months, and IT professionals are concerned that the situation may not improve in 2022.

That dire outlook comes from a newly released survey of more than 1,300 IT professionals worldwide from the Information Systems Audit and Control Association (ISACA). More than half of those surveyed said they expect the number of supply chain hacks to stay the same or worsen this year.

Of those surveyed, 39% said their company does not have an incident response plan set up with suppliers in case of a cyberattack, and 53% said they don’t perform vulnerability scanning or penetration testing on their providers. In all, 84% said their organization’s supply chain needs better governance.

Industry veteran Rob Clyde, formerly the chair of ISACA’s board and a former CTO of Symantec, called the survey’s results “a little bit alarming.” The good news is that companies have started to pay more attention to the security of the supply chain since the hack of SolarWinds, first reported in December 2020, and the increase in remote work during the pandemic.

The upside: “Most large organizations have a CISO,” says Clyde. “Most boards do in fact meet regularly about cybersecurity, something that did not happen five or six years ago.”

The upside: “Most large organizations have a CISO,” says Clyde. “Most boards do in fact meet regularly about cybersecurity, something that did not happen five or six years ago.”

The cybercrime that firms are up against

The challenge is that individual hackers, organized crime rings, and sophisticated nation-states are often working in parallel. The SolarWinds cyberattack has been attributed to hackers, backed by Russian intelligence services, who were able to insert malicious software into a routine update of code meant to monitor clients’ networks. An estimated 18,000 companies and government agencies may have been affected by the attack.

We live in a world where the attacker’s job is actually far easier: [They] find one way in.

With ample resources, bad actors are even more innovative about how they burrow deep inside a company’s supply chain, Clyde says. They can recruit a developer already working at a software company to insert malicious code, or try to get their own hacker hired at the company. Their labs can run test attacks on every state-of-the-art cybersecurity product on the market.

“We live in a world where the attacker’s job is actually far easier: [They] find one way in,” Clyde says. Cybersecurity professionals, in contrast, have to be alert for all possible avenues that someone could exploit and design ways to prevent any of them.

The job has only been complicated by the surge in remote work during the pandemic, which greatly increased the number of devices connected to a company’s network from the outside. The pandemic eliminated the idea that an impenetrable firewall could possibly protect a company.

Shoring up your defenses

Basic cyber hygiene—including endpoint inventories, performance monitoring, and patching and configuration management—offers a significant level of security. Along these lines, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) issued updated guidance in May 2022 for securing enterprises against supply chain hacks. Its 326 pages of free concrete advice were long awaited as a way to make President Biden’s cybersecurity executive order a reality. They detail scenarios and contingency plans for supply chain risks ranging from evaluating foreign control over a software or product’s development to those associated with using external IT service providers.

“Managing the cybersecurity of the supply chain is a need that is here to stay,” said NIST’s Jon Boyens, one of the publication’s authors, in an interview with Bleeping Computer. “If your agency or organization hasn’t started on it, this is a comprehensive tool that can take you from crawl to walk to run, and it can help you do so immediately.” According to NIST, cyber hygiene comes down to trust and confidence. Organizations need to have greater assurance that what they are purchasing and using is trustworthy.This is a comprehensive tool that

can take you from crawl to walk

to run, and it can help you do

so immediately.

[Read also: Cyber Hygiene 101]

ISACA, in its report, offered five additional steps that IT professionals can take to help protect their organizations from supply chain attacks:

- Inventory suppliers and their capabilities, including a

risk-classification of how valuable each supplier is to a

company’s operations.. - Require suppliers to disclose the open-source components contained in the products and services they provide.

- Perform a threat and vulnerability analysis of key third parties to identify possible security risks and their potential impacts.

- Include security expectations and requirements in contracts with suppliers.

- Conduct evidence-based reviews of key third parties.

The last suggestion is essential when it comes to major suppliers, Clyde says. Too often, companies simply send suppliers a questionnaire about the security of their software, asking whether developers use two-factor authentication, how they secure endpoints, and which security tests they have performed.

You’re basically taking a supplier at its word, and that isn’t enough, Clyde says. If a supplier’s software is on most of your systems, has access to your most valuable data, or would cause a major impact on your operations if it were hacked, you need to scrutinize a supplier much more closely.

[Read also: Supply chain security is tough—so what should good look like?]

“I would like to see an audit report,” Clyde says, but only 56% of the executives in the ISACA survey perform audit assessments. With a major supplier, you could even request a demonstration of its bill of health, Clyde suggests, including evidence that the supplier actually runs its software through certain tests.

If you generate little business for a supplier, it may balk at spending the time and money to do audit reports or tests. “But if you’re spending a lot of money with them, you could even consider sending in your own auditors,” Clyde says.

There’s really “no excuse” for failing to use some type of multifactor authentication throughout the supply chain, he says. Clyde is a “big fan” of web isolation, also known as browser isolation, which refers to technology that protects against malware by keeping internet browsing separate from an endpoint device. He also recommends trusted-app tools that prevent nonapproved software from

being downloaded.

[Read also: How global power leader Cummins embraces cyber hygiene]

A company’s best defense against a supply chain hack is the support of its top executives, so that IT professionals have the resources

to conduct the necessary security assessments of third parties. Anytime an organization does a security assessment or external audit, executives should be asking whether staff evaluated the

supply chain.

Making sure you’re asking hard questions like these is half the

battle. The remainder of an effective defense involves effectively answering them.